Purpose

The Catherine Bergego Scale is a standardized checklist to detect presence and degree of unilateral neglect during observation of everyday life situations. The scale also measures self-awareness of behavioral neglect (anosognosia).

In-Depth Review

Purpose of the measure

The Catherine Bergego Scale is a standardized checklist to detect presence and degree of neglect during observation of everyday life situations. The scale also provides a measure of neglect self-awareness (anosognosia).

Available versions

There is only one version of the CBS. The CBS is comprised of a 10-item checklist for use by clinicians, and a corresponding patient-administered questionnaire that can be used to measure self-awareness of neglect (anosognosia).

Features of the measure

Items:

The CBS is comprised of 10 everyday tasks that the therapist observes during performance of self-care activitiesAs defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, activity is the performance of a task or action by an individual. Activity limitations are difficulties in performance of activities. These are also referred to as function.

. The therapist scores the patient on the following items:

- Forgets to groom or shave the left part of his/her face

- Experiences difficulty in adjusting his/her left sleeve or slipper

- Forgets to eat food on the left side of his/her plate

- Forgets to clean the left side of his/her mouth after eating

- Experiences difficulty in looking towards the left

- Forgets about a left part of his/her body (e.g. forgets to put his/her upper limb on the armrest, or his/her left foot on the wheelchair rest, or forgets to use his/her left harm when he/she needs to)

- Has difficulty in paying attention to noise or people addressing him/her from the left

- Collides with people or objects on the left side, such as doors or furniture (either while walking or driving a wheelchair)

- Experiences difficulty in finding his/her way towards the left when traveling in familiar places or in the rehabilitation unit

- Experiences difficulty finding his/her personal belongings in the room or bathroom when they are on the left side

There is a corresponding patient/carer questionnaire that can be used to assess anosognosia (i.e. self-awareness of neglect). The questionnaire is comprised of 10 questions that correspond with CBS items. For instance, in accordance with the first item the clinician would ask the patient: “do you sometimes forget to groom or shave the left side of your face?” If the patient identifies that the difficulty is present, the clinician asks: “do you find this difficulty mild, moderate or severe?”

Scoring:

The CBS uses a 4-point rating scale to indicate the severity of neglect for each item:

0 = no neglect

1 = mild neglect (patient always explores the right hemispace first and slowly or hesitantly explores the left side)

2 = moderate neglect (patient demonstrates constant and clear left-sided omissions or collisions)

3 = severe neglect (patient is only able to explore the right hemispace)

This results in a total score out of 30.

Azouvi et al. (2002, 2003) have reported arbitrary ratings of neglect severity according to total scores:

0 = No behavioral neglect

1-10 = Mild behavioral neglect

11-20 = Moderate behavioral neglect

21-30 = Severe behavioral neglect

In cases of severe impairment the patient may not able to perform an item of the CBS. In these instances the item is considered invalid, is not scored, and is not included in the final score. As such, the total score would be a calculation of the average score of the valid questions (i.e. sum of individual scores divided by number of valid questions x 10).

The patient questionnaire also uses a 4-point rating scale according to the following levels of difficulty experienced by the patient:

0 = no difficulty

1 = mild difficulty

2 = moderate difficulty

3 = severe difficulty

The anosognosia score is then calculated as the difference between the clinician’s total score and the patient’s self-assessment score (Azouvi et al., 2003):

Anosognosia score = clinician’s CBS score – patient’s self-assessment score

Description of tasks:

The clinician observes the patient performing self-care activitiesAs defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, activity is the performance of a task or action by an individual. Activity limitations are difficulties in performance of activities. These are also referred to as function.

and provides a score for each of the 10 items according to observations of neglect behaviors (Plummer et al., 2003).

What to consider before beginning:

The items of the CBS vary in their degree of difficulty (tasks listed from least difficult to most difficult, with item numbers indicated in parentheses): cleaning mouth after a meal (item 4); grooming (1) / auditory attention (7); eating (3); spatial orientation (9); gaze orientation (5); finding personal belongings (10); collides when moving (8); left limb knowledge (6); dressing (2). Note that two items (grooming, auditory attention) share the same level of difficulty (Azouvi et al., 2003).

Time:

The CBS takes approximately 30 minutes to administer.

Training requirements:

There are no formal training requirements for administration of the CBS.

Equipment:

The clinician requires the form, a pen and household equipment used to perform the tasks (e.g. razor, brush, toothbrush, clothing, mealtime utensils, serviette). The test can be administered in the patient’s own environment or in the rehabilitation setting.

Alternative forms of the assessment

There are no alternative forms of the CBS.

Client suitability

Can be used with:

- Patients with stroke and hemispatial neglect. While the authors specify use of the CBS with patients with right hemispatial neglect, it may be modified for use with individuals with left hemispatial neglect (Plummer et al., 2003).

Should not be used with:

- The CBS requires patients to perform upper limb and lower limb movements in various testing positions for approximately 30 minutes (Menon & Korner-Bitensky, 2004). While scoring can be adjusted for patients who are not able to perform all tasks, the clinician must consider whether these difficulties are due to neglect or other neurological deficits such as apraxia (Azouvi et al., 1996; Menon & Korner-Bitensky, 2004).

Languages of the measure

English, French, Portuguese

Summary

| What does the tool measure? |

The CBS measures unilateral behavioural neglect. |

| What types of clients can the tool be used for? |

The CBS is designed for use with individuals with stroke who have hemispatial neglect. |

Is this a screeningTesting for disease in people without symptoms.

or assessment tool? |

Assessment. |

| Time to administer |

The CBS takes approximately 30 minutes to administer. |

| Versions |

There is one version of the CBS checklist for use by clinicians. There is also a patient-administered questionnaire that can be used to measure self-awareness of neglect (anosognosia). |

| Languages |

English, French, Portuguese |

| Measurement Properties |

ReliabilityReliability can be defined in a variety of ways. It is generally understood to be the extent to which a measure is stable or consistent and produces similar results when administered repeatedly. A more technical definition of reliability is that it is the proportion of "true" variation in scores derived from a particular measure. The total variation in any given score may be thought of as consisting of true variation (the variation of interest) and error variation (which includes random error as well as systematic error). True variation is that variation which actually reflects differences in the construct under study, e.g., the actual severity of neurological impairment. Random error refers to "noise" in the scores due to chance factors, e.g., a loud noise distracts a patient thus affecting his performance, which, in turn, affects the score. Systematic error refers to bias that influences scores in a specific direction in a fairly consistent way, e.g., one neurologist in a group tends to rate all patients as being more disabled than do other neurologists in the group. There are many variations on the measurement of reliability including alternate-forms, internal consistency , inter-rater agreement , intra-rater agreement , and test-retest .

|

Internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency.:

Five studies have examined the internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency. of the CBS and have reported adequate to excellent internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency., using Spearman rank.

Test-retest:

No studies have reported on the test-retest reliabilityA way of estimating the reliability of a scale in which individuals are administered the same scale on two different occasions and then the two scores are assessed for consistency. This method of evaluating reliability is appropriate only if the phenomenon that the scale measures is known to be stable over the interval between assessments. If the phenomenon being measured fluctuates substantially over time, then the test-retest paradigm may significantly underestimate reliability. In using test-retest reliability, the investigator needs to take into account the possibility of practice effects, which can artificially inflate the estimate of reliability (National Multiple Sclerosis Society).

of the CBS.

Intra-rater:

No studies have reported on the intra-rater reliabilityThis is a type of reliability assessment in which the same assessment is completed by the same rater on two or more occasions. These different ratings are then compared, generally by means of correlation. Since the same individual is completing both assessments, the rater's subsequent ratings are contaminated by knowledge of earlier ratings.

of the CBS.

Inter-rater:

One study examined the inter-rater reliabilityA method of measuring reliability . Inter-rater reliability determines the extent to which two or more raters obtain the same result when using the same instrument to measure a concept.

of the CBS and reported adequate to excellent inter-rater reliabilityA method of measuring reliability . Inter-rater reliability determines the extent to which two or more raters obtain the same result when using the same instrument to measure a concept.

, using kappa and correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficients.

|

ValidityThe degree to which an assessment measures what it is supposed to measure.

|

Internal validityThe degree to which an assessment measures what it is supposed to measure.

:

One study has examined the internal validity of the CBS and found unidimensionality of items by Rasch analysisRasch analysis is a statistical measurement method that allows the measurement of an attribute - such as upper limb function - independently of particular tests or indices.  It creates a linear representation using many individual items, ranked by item difficulty (e.g. picking up a very small item, versus a task requiring a very gross grasp) and person ability.   A well performing Rasch model will have items hierarchically placed from simple to more difficult, and individuals with high abilities should be able to perform all the items below a level of difficulty. The Rasch model is statistically strong because it enables ordinal measures to be converted into meaningful interval measures. It also allows information from various tests or tools with different scoring systems to be applied using the Rasch model.

.

Content:

No studies have reported on the content validityRefers to the extent to which a measure represents all aspects of a given social concept. Example: A depression scale may lack content validity if it only assesses the affective dimension of depression but fails to take into account the behavioral dimension.

of the CBS.

Criterion:

Concurrent:

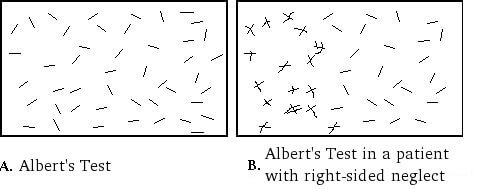

– Five studies has examined the concurrent validityTo validate a new measure, the results of the measure are compared to the results of the gold standard obtained at approximately the same point in time (concurrently), so they both reflect the same construct. This approach is useful in situations when a new or untested tool is potentially more efficient, easier to administer, more practical, or safer than another more established method and is being proposed as an alternative instrument. See also "gold standard."

of the CBS with other neglect tasks in patients with right hemisphere stroke and reported excellent correlations with Albert’s Test, Behavioral Inattention Test subtests, the Bells test, a reading task and a writing task. Adequate to excellent correlations were reported with Ogden’s scene drawing task, overlapping figures and a daisy drawing task. Poor to adequate correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

were reported with Bisiach et al.’s (1986) scale of awareness of visual and motor neglect.

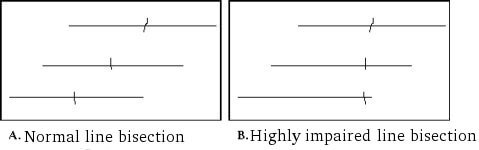

– One study has examined the concurrent validityTo validate a new measure, the results of the measure are compared to the results of the gold standard obtained at approximately the same point in time (concurrently), so they both reflect the same construct. This approach is useful in situations when a new or untested tool is potentially more efficient, easier to administer, more practical, or safer than another more established method and is being proposed as an alternative instrument. See also "gold standard."

of the CBS with other neglect tasks in patients with left hemisphere stroke and reported adequate correlations with the Bells test, but no significant correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

with a line bisection test.

Predictive:

No studies have reported on the predictive validityA form of criterion validity that examines a measure's ability to predict some subsequent event. Example: can the Berg Balance Scale predict falls over the following 6 weeks? The criterion standard in this example would be whether the patient fell over the next 6 weeks.

of the CBS.

Construct:

One study conducted a factor analysis and revealed one underlying factor.

Convergent/Discriminant:

Two studies have examined the convergent validityA type of validity that is determined by hypothesizing and examining the overlap between two or more tests that presumably measure the same construct. In other words, convergent validity is used to evaluate the degree to which two or more measures that theoretically should be related to each other are, in fact, observed to be related to each other.

of the CBS and reported an excellent correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

with the Barthel Index and an adequate correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

with the Functional Independence Measure and the Postural Assessment for StrokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain. Scale, using Spearman’s rank correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficient.

Known Groups:

Two studies have examined the known groups validityKnown groups validity is a form of construct validation in which the validity is determined by the degree to which an instrument can demonstate different scores for groups know to vary on the variables being measured.

of the CBS and reported that the CBS is able to distinguish between patients with/without neglect and patients with/without visual field deficits. The CBS does not differentiate between patients with/without depressionIllness involving the body, mood, and thoughts, that affects the way a person eats and sleeps, the way one feels about oneself, and the way one thinks about things. A depressive disorder is not the same as a passing blue mood or a sign of personal weakness or a condition that can be wished away. People with a depressive disease cannot merely "pull themselves together" and get better. Without treatment, symptoms can last for weeks, months, or years. Appropriate treatment, however, can help most people with depression.

. |

| Floor/Ceiling Effects |

One study reported adequate floor/ceiling effects.

|

| Does the tool detect change in patients? |

Two studies have reported that the CBS can detect change in neglect. |

| Acceptability |

Not reported |

| Feasibility |

The CBS is straightforward and easy to administer. While there is no formal training, administration of the CBS requires clinicians to possess a sound understanding of neglect and its behavioral manifestations. There is no manual to aide administration or scoring. |

| How to obtain the tool? |

The CBS can be accessed in the article by Azouvi et al. (1995). |

Psychometric Properties

Overview

A literature search was conducted to identify all relevant publications on the psychometric properties of the Catherine Bergego Scale (CBS). Eight articles were reviewed.

Floor/Ceiling Effects

Azouvi et al. (2003) reported that 3.6% of patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain. achieved a total CBS score of 0 (no neglect), indicating an adequate floor/ceiling effect.

Reliability

Internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency.:

Bergego et al. (1995) examined the internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency. of the CBS with 18 patients with right hemisphere stroke and reported adequate to excellent correlations between the total score and all items (rho range = 0.48 – 0.87, p<0.05).

Azouvi et al. (1996) examined the internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency. of the CBS with 50 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain., using Spearman rank correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficients. An adequate correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

was found between the CBS total score and the “mouth cleaning” item (rho=0.58, p<0.0001). An excellent correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

was found between the total score and all other items (rho range from 0.69 – 0.88, p<0.0001). An adequate correlation was found between the therapist’s score and the patient’s self-evaluation (rho = 0.52, p<0.001). There was an excellent correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

between the therapist’s score and the anosognosia score (i.e. therapist’s total score – patient’s self-evaluation score) (rho = 0.75, p<0.0001).

Azouvi et al. (2002) examined the anosognosia component of the CBS in 69 patients with subacute right hemisphere stroke. Patients’ self-assessment score was significantly lower than the examiner’s score (p<0.0001). There was an excellent correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

between the therapist’s score (neglect severity) and the anosognosia score (r=0.82, p<0.0001).

Azouvi et al. (2003) examined the internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency. of the CBS with 83 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain. and reported adequate to excellent correlations between items (correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficient range = 0.48 – 0.73, p<0.0001). Patients’ self-assessment scores were significantly lower than examiners’ total CBS scores (p<0.0001). An excellent correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

was found between the therapist’s score (neglect severity) and the anosognosia score (r=0.79, p<0.0001). Patients with moderate or severe neglect achieved high anosognosia scores, whereas patients with mild or no neglect achieved negative scores, indicating higher self-rating of severity than scores attributed by the therapist.

Luukkainen-Markkula et al. (2011) examined the internal consistencyA method of measuring reliability . Internal consistency reflects the extent to which items of a test measure various aspects of the same characteristic and nothing else. Internal consistency coefficients can take on values from 0 to 1. Higher values represent higher levels of internal consistency. of the CBS using Spearman correlations. There were adequate< to excellent correlations between the CBS total score and all item scores, except for the “eating” item (grooming: r=0.64, p<0.05; mouth cleaning: r=0.73, p<0.05; gaze orientation: r=0.80, p<0.01; knowledge of left limbs: r=0.61, p<0.05; auditory attention: r=0.89, p<0.01; collisions when moving: r=0.89, p<0.01; spatial orientation: r=0.89, p<0.01; dressing: r=0.51, p<0.05; finding personal belongings: r=-0.66, p<0.05). Adequate to excellent correlations were also reported between many CBS items (r range from 0.51 to 0.94, p<0.05 to p<0.01).

Azouvi et al. (2003) examined the reliabilityReliability can be defined in a variety of ways. It is generally understood to be the extent to which a measure is stable or consistent and produces similar results when administered repeatedly. A more technical definition of reliability is that it is the proportion of "true" variation in scores derived from a particular measure. The total variation in any given score may be thought of as consisting of true variation (the variation of interest) and error variation (which includes random error as well as systematic error). True variation is that variation which actually reflects differences in the construct under study, e.g., the actual severity of neurological impairment. Random error refers to "noise" in the scores due to chance factors, e.g., a loud noise distracts a patient thus affecting his performance, which, in turn, affects the score. Systematic error refers to bias that influences scores in a specific direction in a fairly consistent way, e.g., one neurologist in a group tends to rate all patients as being more disabled than do other neurologists in the group. There are many variations on the measurement of reliability including alternate-forms, internal consistency , inter-rater agreement , intra-rater agreement , and test-retest .

of the CBS. The item reliabilityReliability can be defined in a variety of ways. It is generally understood to be the extent to which a measure is stable or consistent and produces similar results when administered repeatedly. A more technical definition of reliability is that it is the proportion of "true" variation in scores derived from a particular measure. The total variation in any given score may be thought of as consisting of true variation (the variation of interest) and error variation (which includes random error as well as systematic error). True variation is that variation which actually reflects differences in the construct under study, e.g., the actual severity of neurological impairment. Random error refers to "noise" in the scores due to chance factors, e.g., a loud noise distracts a patient thus affecting his performance, which, in turn, affects the score. Systematic error refers to bias that influences scores in a specific direction in a fairly consistent way, e.g., one neurologist in a group tends to rate all patients as being more disabled than do other neurologists in the group. There are many variations on the measurement of reliability including alternate-forms, internal consistency , inter-rater agreement , intra-rater agreement , and test-retest .

index was 0.93, resulting in 3.5 strata of significantly different difficulty (p<0.05). Although most items vary in their degree of difficulty, 2 items (grooming, auditory attention), share the same level of difficulty. The person reliability index was 0.88, resulting in 2.7 statistically different levels of ability (p<0.05).

Azouvi et al. (2003) examined the internal structure of the CBS by Rasch analysisRasch analysis is a statistical measurement method that allows the measurement of an attribute - such as upper limb function - independently of particular tests or indices.  It creates a linear representation using many individual items, ranked by item difficulty (e.g. picking up a very small item, versus a task requiring a very gross grasp) and person ability.   A well performing Rasch model will have items hierarchically placed from simple to more difficult, and individuals with high abilities should be able to perform all the items below a level of difficulty. The Rasch model is statistically strong because it enables ordinal measures to be converted into meaningful interval measures. It also allows information from various tests or tools with different scoring systems to be applied using the Rasch model.

. Item 2 (dressing) obtained an outlier outfit value (mnsq = 0.58), indicating potential redundancy of this item due to too little variance. Overall mean fit scores were very close to 1.00, supporting unidimensionality. This is further supported by high positive-point biserial correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficients (i.e. the extent to which the items correlate with the linear measure) between each item score, and cumulative scores obtained across the whole sample.

Test-retest:

No studies have reported on the test-retest reliabilityA way of estimating the reliability of a scale in which individuals are administered the same scale on two different occasions and then the two scores are assessed for consistency. This method of evaluating reliability is appropriate only if the phenomenon that the scale measures is known to be stable over the interval between assessments. If the phenomenon being measured fluctuates substantially over time, then the test-retest paradigm may significantly underestimate reliability. In using test-retest reliability, the investigator needs to take into account the possibility of practice effects, which can artificially inflate the estimate of reliability (National Multiple Sclerosis Society).

of the CBS.

Intra-rater:

No studies have reported on the intra-rater reliabilityThis is a type of reliability assessment in which the same assessment is completed by the same rater on two or more occasions. These different ratings are then compared, generally by means of correlation. Since the same individual is completing both assessments, the rater's subsequent ratings are contaminated by knowledge of earlier ratings.

of the CBS.

Inter-rater :

Bergego et al. (1995) examined the inter-rater reliabilityA method of measuring reliability . Inter-rater reliability determines the extent to which two or more raters obtain the same result when using the same instrument to measure a concept.

of the CBS among 18 patients and found adequate to excellent inter-rater reliabilityA method of measuring reliability . Inter-rater reliability determines the extent to which two or more raters obtain the same result when using the same instrument to measure a concept.

for the 10 items (kappa coefficient range = 0.59 – 0.99). CorrelationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

between the two examiners’ total scores, measured by Spearman rank correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficient, was excellent (rho = 0.96, p<0.0001).

Validity

Content:

No studies have reported on the content validityRefers to the extent to which a measure represents all aspects of a given social concept. Example: A depression scale may lack content validity if it only assesses the affective dimension of depression but fails to take into account the behavioral dimension.

of the CBS.

Criterion:

Concurrent:

Bergego et al. (1995) compared the CBS total score with other conventional neglect tests in 18 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain., using Spearman rank correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficients. Excellent correlations were reported between the CBS and the Bells test, Ogden’s scene drawing task, writing task, reading task and Albert’s Test (rho = 0.72, 0.72, 0.72, 0.70 and 0.67 respectively, p<0.01). There was no statistically significant correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

with a flower drawing task.

Azouvi et al. (1996) compared the CBS total score with other conventional neglect tests among 50 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain., using Spearman rank correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficients. Excellent correlations were found between the CBS and the Bells test (rho = 0.74, p<0.0001), Albert’s Test (line cancellation) (rho = 0.73, p<0.0001) and a reading task (rho = 0.61, p<0.0001). Adequate correlations were found with the Ogden’s scene drawing task (rho = 0.56, p<0.001) and a daisy drawing task (rho = 0.50, p<0.001). Adequate correlations were found between the CBS anosognosia score and conventional tests of neglect (rho range = 0.45 – .58, p<0.01). A weak correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

was found between the CBS anosognosia score and Bisiach et al.’s (1986) scale of patients’ awareness of neurological deficit (rho = 0.31, p<0.05).

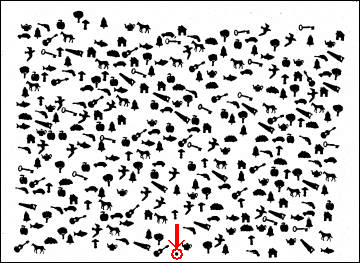

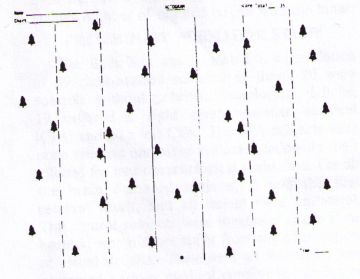

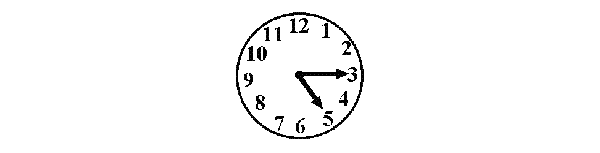

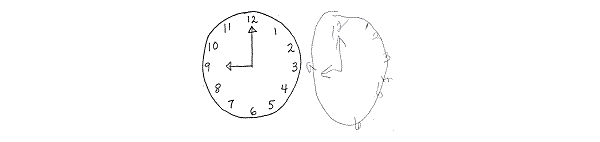

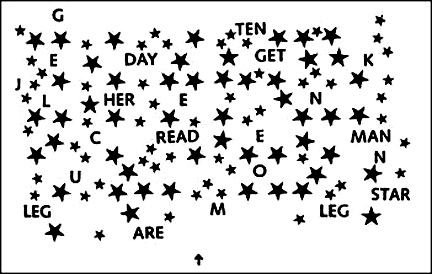

Azouvi et al. (2002) compared the CBS with a battery of conventional pen and paper neglect tasks among 69 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain.. Conventional neglect tasks included the Bells test, a figure-copying task, clock drawing, line bisection tasks (5cm, 20cm), overlapping figures test, reading task and a writing task. There were adequate to excellent correlations between the CBS and all conventional neglect tasks (r range = 0.49 – 0.77, p<0.0001), except for the short (5cm) line bisection task. The strongest correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

was seen with the Bells test (total number of omissions). Further stepwise multiple regression analysis revealed that four conventional neglect tasks – the total number of omissions in the Bells test, starting point in the Bells test, figure copying task and the clock drawing task – significantly predict behavioral neglect. Moderate to excellent correlations were found between the CBS anosognosia score and all conventional neglect tasks (r range = 0.47 – 0.70, p<0.0001), except the short (5cm) line bisection task. Comparison with Bisiach et al.’s (1986) scale of visual and motor anosognosia found a moderate correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

with visual anosognosia (r=0.37, p<0.05), but a poor correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

with motor anosognosia (r=0.29, p<0.05).

Azouvi et al. (2003) compared the CBS total score with three conventional neglect tasks in 83 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain.. Excellent correlations were found with the Bells test (number of omissions) (r=0.76, p<0.0001) and a figure-copying task (r=0.70, p<0.0001), and an adequate correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

was found with a short reading task (number of omissions) (r=0.54, p<0.0001). Comparison of the CBS anosognosia scores with conventional neglect tasks revealed adequate to excellent correlations (r range = 0.43 – 0.72, p<0.01).

Azouvi et al. (2006) reported on unpublished data from 54 patients with left hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain.. There was an adequate correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

between the CBS score and the Bells test – total omissions (r=0.41, p<0.01) and right minus left omissions (r=0.34, p<0.01). There was no significant correlation with a line bisection test.

Luukkainen-Markkula et al. (2011) compared the CBS with the conventional subtests of the Behavioral Inattention Test (BIT C) among 17 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain. and hemispatial neglect. Only the BIT C line bisection subtest showed statistically significant correlations with the CBS, demonstrating excellent correlations with the grooming (r=-0.64, p≤0.01) and gaze orientation (-0.61, p≤0.01) subtests, and adequate correlations with the auditory attention (r=-0.56, p≤0.05) and spatial orientation (r=-0.54, p≤0.05) subtests and the CBS total score (r=-0.54, p≤0.05). Conversely, the CBS eating item was the only item to demonstrate statistically significant correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

with the BIT C, revealing excellent correlations with the line crossing (r=-0.95, p≤0.01), letter cancellation (r=0.83, p≤0.01) and star cancellation (r=-0.83, p≤0.01) subtests and the BIT C total score (r=-0.83, p≤0.01).

Despite significant correlations between the CBS and traditional visual neglect tests, individual patients can demonstrate dissociations between visual and behavioral neglect (Azouvi et al., 1995, 2002, 2006; Luukkainen-Markkula et al., 2011).

Predictive:

No studies have reported on the predictive ability of the CBS.

Construct:

Azouvi et al. (2003) conducted a conventional factor analysis on raw scores, revealing a single underlying factor that explained 65.8% of total variance. The factor matrix showed that all 10 items obtained a high loading on this factor (range = 0.77 – 0.84). Further, principal component analysis on standardized residuals after the linear method was extracted showed that no strong factors remained hidden in the residuals between observed and expected scores.

Convergent/Discriminant :

Azouvi et al. (1996) examined the ability of the CBS to measure aspects of daily functioning related to neglect by comparing CBS and Barthel Index scores of 50 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain., using Spearman’s rank correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

coefficient. An excellent correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

was found between CBS total score and the Barthel Index (rho = -0.63, p<0.0001).

Azouvi et al. (2006) reported on unpublished data from 54 patients with left hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain.. There was an adequate correlationThe extent to which two or more variables are associated with one another. A correlation can be positive (as one variable increases, the other also increases - for example height and weight typically represent a positive correlation) or negative (as one variable increases, the other decreases - for example as the cost of gasoline goes higher, the number of miles driven decreases. There are a wide variety of methods for measuring correlation including: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC), the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the Spearman rank-order correlation.

between the CBS score and the Functional Independence Measure (r=-0.48, p<0.01), and the Postural Assessment for StrokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain. Scale (r=-0.55, p<0.001).

Known Group:

Azouvi et al. (1996) compared behavioral neglect in patients with neglect on conventional tests and patients with no neglect, using Mann Whitney tests. There was a significant difference in total CBS scores between the two groups (p<0.0001). Comparison of anosognosia revealed a significant difference between groups (p<0.001), whereby patients with no neglect tended to overestimate their difficulties (compared to the difficulties reported by the therapist) and patients with neglect tended to underestimate their neglect difficulties.

Azouvi et al. (1996) reported no significant difference in CBS anosognosia scores between patients with depressionIllness involving the body, mood, and thoughts, that affects the way a person eats and sleeps, the way one feels about oneself, and the way one thinks about things. A depressive disorder is not the same as a passing blue mood or a sign of personal weakness or a condition that can be wished away. People with a depressive disease cannot merely "pull themselves together" and get better. Without treatment, symptoms can last for weeks, months, or years. Appropriate treatment, however, can help most people with depression.

and patients without depressionIllness involving the body, mood, and thoughts, that affects the way a person eats and sleeps, the way one feels about oneself, and the way one thinks about things. A depressive disorder is not the same as a passing blue mood or a sign of personal weakness or a condition that can be wished away. People with a depressive disease cannot merely "pull themselves together" and get better. Without treatment, symptoms can last for weeks, months, or years. Appropriate treatment, however, can help most people with depression.

.

Luukkainen-Markkula et al. (2011) compared behavioral neglect in patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain. and hemispatial neglect with visual field deficits (n=8) and patients with intact visual fields (n=9), using Mann Whitney tests. Patients with visual field deficits demonstrated significantly more severe behavioral neglect (i.e. higher CBS total score) than patients with intact visual fields (p=0.03).

Responsiveness

Samuel et al. (2000) reported that the CBS is responsive to clinical change following visuo-spatio-motor cueing intervention in patients with strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain. and unilateral spatial neglect.

SensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

:

Azouvi et al (1995) examined the sensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

of the CBS by determining the ability of each CBS item to detect the presence of neglect (i.e. a score of 1 or more) in a group of 50 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain.. The most sensitive items at detecting neglect were items 2 (dressing), 4 (knowledge of left limbs) and 8 (collisions while moving), which all demonstrated neglect in more than 50% of patients. SensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

of other items in descending order was as follows: item 1 (grooming), 3 (eating), 10 (personal belongings), 5 (gaze orientation), 7 (auditory attention), 9 (spatial orientation) and 4 (mouth cleaning). The CBS was more sensitive to neglect than conventional neglect tasks (Bells test, reading task, line cancellation test), which were found to detect neglect in 42 – 49% of patients.

Azouvi et al. (2002) examined the sensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

of the CBS among 69 patients with right hemisphere neglect. Similar to their earlier study (Azouvi et al., 1995), the most sensitive items were item 4 (knowledge of left limbs), item 8 (collisions) and item 2 (dressing). The authors compared the sensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

of the CBS with a battery of conventional neglect tasks that comprised the Bells test, a figure copying task, clock drawing, line bisection task, overlapping figures test, reading task and a writing task. Stepwise multiple regression analysis revealed that four conventional neglect tasks – the total number of omissions in the Bells test, starting point in the Bells test, figure copying task and the clock drawing task – significantly predict behavioral neglect. These tasks revealed neglect in 71.84% of patients, but did not indicate neglect in 16.38% of patients who demonstrated neglect on the CBS. The highest incidence of neglect in conventional tests was 50%, whereas neglect was seen on at least 1 of the 10 CBS items in 76% of patients. This indicates that the CBS was more sensitive to neglect, although the difference in sensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

between the CBS and the battery of conventional neglect tasks was not statistically significant.

Azouvi et al. (2003) compared the sensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

of the CBS to three conventional neglect tasks in 83 patients with right hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain.. Incidence of neglect on individual conventional tasks was 44.3% on a figure copying task, 53.8% on the Bells Test and 64.2% on a reading task; 65.4% of participants showed neglect on at least one conventional neglect task and 32.7% of participants showed neglect on all three tasks. By comparison, 96.4% of participants demonstrated neglect based on total CBS score. SensitivitySensitivity refers to the probability that a diagnostic technique will detect a particular disease or condition when it does indeed exist in a patient (National Multiple Sclerosis Society). See also "Specificity."

of individual CBS items ranged from 49.5% (auditory attention, spatial orientation) to 79.5% (dressing).

Azouvi et al. (2006) reported on unpublished data from 54 patients with left hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain., which showed that 77.3% of patients showed neglect on one item of the CBS scale. Only 5.4% of patients showed clinically significant neglect, compared to 36% of patients with right hemisphere neglect reported in an earlier study by Azouvi et al. (2002). The three items “neglect of right limbs’, “dressing” and “mouth cleaning after eating” showed higher incidence of neglect among patients with left hemisphere strokeAlso called a "brain attack" and happens when brain cells die because of inadequate blood flow. 20% of cases are a hemorrhage in the brain caused by a rupture or leakage from a blood vessel. 80% of cases are also know as a "schemic stroke", or the formation of a blood clot in a vessel supplying blood to the brain., whereas the item “collisions while moving” obtained lower neglect scores. This is in contrast to earlier studies with patients with right hemisphere neglect (Azouvi et al., 1996, 2002).

References

- Azouvi, P., Bartolomeo, P., Beis, J-M., Perennou, D., Pradat-Diehl, P., & Rousseaux, M. (2006). A battery of tests for the quantitative assessment of unilateral neglect. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 24, 273-85.

- Azouvi, P., Marchal, F., Samuel, C., Morin, L., Renard, C., Louis-Dreyfus, A., Jokie, C., Wiart, L., Pradat-Diehl, P., Deloche, G., & Bergego, C. (1996). Functional consequences and awareness of unilateral neglect: Study of an evaluation scale. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 6(2), 133-150.

- Azouvi, P., Olivier, S., de Montety, G., Samuel, C., Louis-Dreyfus, A., & Tesio, L. (2003). Behavioral assessment of unilateral neglect: Study of the psychometric properties of the Catherine Bergego Scale. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 84, 51-7.

- Azouvi, P., Samuel, C., Louis-Dreyfus, A., Bernati, T., Bartolomeo, P., Beis, J-M., Chokron, S., Leclercq, M., Marchal, F., Martin, Y., de Montety, G., Olivier, S., Perennou, D., Pradat-Diehl, P., Prairial, C., Rode, G., Siéroff, E., Wiart, L., Rousseaux, M. for the French Collaborative Study Group on Assessment of Unilateral Neglect (GEREN/GRECO). (2002). Sensitivity of clinical and behavioral tests of spatial neglect after right hemisphere stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 73, 160-6.

- Bergego, C., Azouvi, P., Samuel, C., Marchal, F., Louis-Dreyfus, A., Jokie, C., Morin, L., Renard, C., Pradat-Diehl, P., & Deloche, G. (1995). Validation d’une échelle d’évaluation fonctionnelle de l’héminegligence dans la vie quotidienne: l’échelle CB. Annales de Readaptation et de Medecine Physique, 38, 183-9.

- Luukkainen-Markkula, R., Tarkka, I.M., Pitkänen, K., Sivenius, J., & Hämäläinen, H. (2011). Comparison of the Behavioral Inattention Test and the Catherine Bergego Scale in assessment of hemispatial neglect. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 21(1), 103-116.

- Menon, A. & Korner-Bitensky, N. (2004). Evaluating unilateral spatial neglect post stroke: Working your way through the maze of assessment choices. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 11(3), 41-66.

- Plummer, P., Morris, M. E., & Dunai, J. (2003). Assessment of unilateral neglect. Physical Therapy, 83, 732-40.

- Samuel, C., Louis-Dreyfus, A., Kaschel, R., Makiela, E., Troubat, M., Anselmi, N., Cannizzo, V., & Azouvi, P. (2000). Rehabilitation of very severe unilateral neglect by visuo-spatio-motor cueing: Two single case studies. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 10(4), 385-99.

See the measure

How to obtain the CBS

The Catherine Bergego Scale (CBS) can be viewed in the journal article:

Azouvi, P., Marchal, F., Samuel, C., Morin, L., Renard, C., Louis-Dreyfus, A., Jokie, C., Wiart, L., Pradat-Diehl, P., Deloche, G., & Bergego, C. (1996). Functional consequences and awareness of unilateral neglect: Study of an evaluation scale. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 6(2), 133-150.